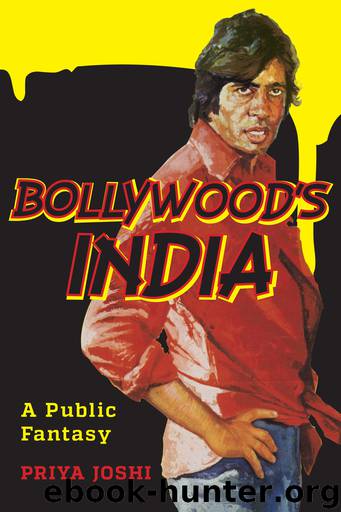

Bollywood's India by Priya Joshi

Author:Priya Joshi [Joshi, Priya]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: PER004030, PERFORMING ARTS / Film & Video / History & Criticism, ART019000, ART / Asian

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2015-02-28T16:00:00+00:00

FIGURES 4.7 AND 4.8 “I won’t leave you; I’ll observe my marital vows.” Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia in Bobby.

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

FIGURE 4.8

The song’s subtext is even more sinister than its physical violence. In the decade before death by fire became the preferred method in dowry murders, “falling” into a well was the preferred way of eliminating a bride who had run her use as a source of dowry.16 Raja’s catalog of commodities he putatively declines in the first song (gold, house, car) rehearses a typical list of dowry demands. Raja and Bobby’s subsequent duet rehearses the preamble to a dowry death. Nothing, not even the threats, are innocent here. On any level, the sadism in the duet counters the utopian vow of true love in the first song, playing out the perils of adolescent love and serving as a cautionary tale of impulsive desire.

While the plot and staging of Kapoor’s blockbuster manifestly celebrate the theme of adolescent passion, the songs interrupt that continuity and latently correct an overt endorsement. The Raja-Bobby duet, “Jhoot boley,” cautions women in particular that leaving the family for a forbidden love is dangerous: love can turn and the woman, always vulnerable, has no recourse or support. Another narrative of social violence is marked behind Bobby’s frothy love story. The conclusion of the Raja-Bobby story re-creates the status quo of the capitalist male (Raja) claiming mastery over working-class labor (the fisherwoman Bobby) that remains typically female (figs. 4.7 and 4.8). That this ominous outcome is gestured in a song (“Jhoot boley”) in which the fashionably modern Bobby is dressed as a fisherwoman under scores that, romantic love notwithstanding, Bobby’s origins indicate her class’s destiny in a union with Raja.

Rather than the two songs appearing to contradict each other, they provide a sobering account of an “ever after” that the commercial film cannot manifestly provide. Bobby’s cinematic closure turns to Hollywood fairytale (the dreamwalk from Wizard of Oz; see fig. 4.3) not because it believes in fairytales. It turns there to point out the fairytale’s necessity against a violence that all fairytales both gesture toward and heroically contain. “They all lived happily ever after” is only comforting if one knows how unhappy ever after they might have been. Creating a space where the violent ever after can be enacted safely, in play, is caution enough. The point is to indicate a threat, not to eradicate it. What Bollywood’s audiences observe in these lyrical interruptions is the even-handed depiction of desire, rather than a contradiction inherent in its representation. This form of narrative irony, where manifest and latent content coexist without apparent disruption to the pleasures of spectacle, is exactly what recedes in later Bollylite productions with their singular narrative planes.

Recognizing the disruption of such narrative moments, Bollywood’s neglect in the United States lies less in American indifference to its stock formulae and musical numbers than in Bombay’s insistence on targeting the interests and preoccupations of its domestic audience. For Bollywood is first and always staunchly grounded in its origins in the Subcontinent.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31374)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30969)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30923)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(22361)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18109)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13142)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12973)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12812)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12479)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11955)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11940)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8394)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7873)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6513)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6434)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5801)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5551)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5077)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4903)